Nearly one in five girls ages fourteen to seventeen has been the victim of a sexual assault or attempted sexual assault. This is the true story of one of those girls.

Nearly one in five girls ages fourteen to seventeen has been the victim of a sexual assault or attempted sexual assault. This is the true story of one of those girls.

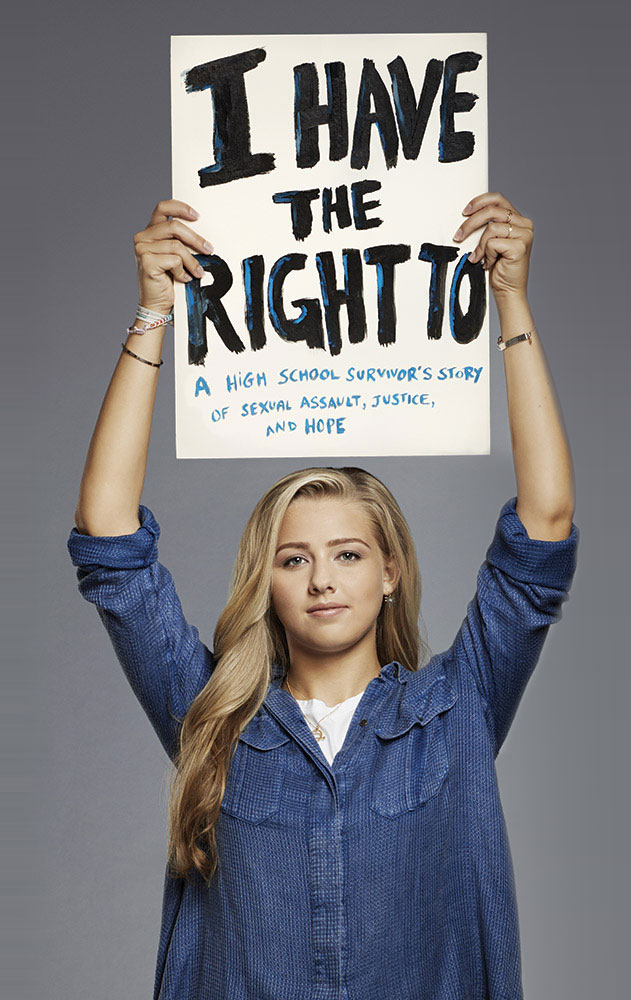

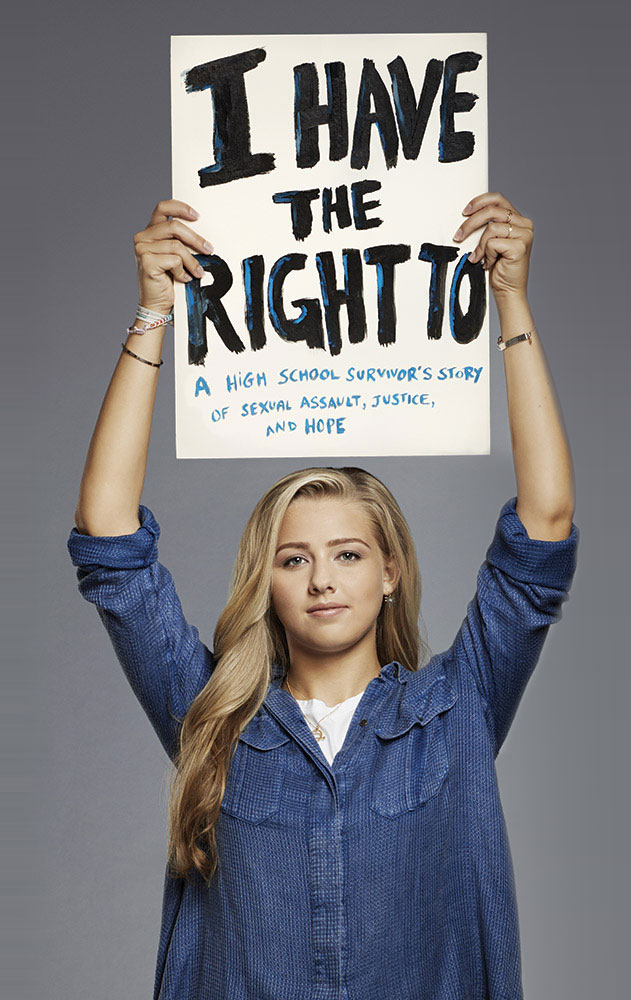

In 2014, Chessy Prout was a freshman at St. Paul’s school, a prestigious boarding school in New Hampshire, when a senior boy sexually assaulted her as part of a ritualized game of conquest. Chessy bravely reported her assault to the police and testified against her attacker in court. Then, in the face of unexpected backlash from her once-trusted school community, she shed her anonymity to help other survivors find their voice.

This memoir is more than an account of a horrific event. It takes a magnifying glass to the institutions that turn a blind eye to such behavior and a society that blames victims rather than perpetrators. Chessy’s story offers real, powerful solutions to upending rape culture as we know it today. Prepare to be inspired by this remarkable young woman and her story of survival, advocacy, and hope in the face of unspeakable trauma.

"Brave, important, and unforgettable, Chessy Prout’s compelling story of her personal survival from sexual assault is a must read for teens, parents, and educators alike; I Have the Right To demands and deserves the right for a place on classroom and library bookshelves everywhere."

—Dr. Rose Brock, College of Education, Sam Houston State University

Download the I Have the Right To educator guide for classroom, library, or reading group use.

Download the I Have the Right To educator guide for classroom, library, or reading group use.There is no road map for victims and families surviving sexual assault. And there is no one way to prepare for a traumatic life event or sexual assault, just as there is no way to prepare for the effects of a devastating earthquake or a life-threatening illness.

In the aftermath of Chessy’s assault, we made some good decisions with careful thought, and other actions we took were made by chance—like not questioning Chessy when she called late that night about why she went with Owen Labrie, or demanding to know why she didn’t tell us sooner. We told her we loved her and we would get through this together, one step at a time. Of course, her older sister Lucy had said the most important words of all, right from the start: It’s not your fault. That her sister knew to respond that way was a blessing, pure and simple.

In the aftermath of trauma, it is critical to find people who will listen, love, and support you. It took us two years to find and speak to another survivor’s parent, and learn about the commonalities all survivors and their families face. The shame confronting many survivors is isolating, and can extend to the family of survivors, affecting every aspect of your lives, from where you live, work, and send your children to school, as you are trying to seek justice and healing.

We tightened and reworked our network of support. We will always be indebted to our family, old friends, several teachers, and other sexual assault survivors who became our new friends and perhaps most inspiring community. We relied heavily on members of our children’s school community in Naples and were grateful for their support.

We were given good advice by Chessy’s counselor in Naples not to rely on the criminal justice system for healing, because that was beyond our control.

Laws differ state by state in terms of how crimes are defined and what victims’ rights are. We immersed ourselves in New Hampshire laws surrounding sexual assault and the court process we would potentially face.

So much depends on the attitudes of the police and district attorney in handling sexual assault cases. The Concord authorities cared about what happened to Chessy, about sexual assault crimes, about high school students in their city, as did the district attorney involved. But we didn’t know what they would make of it, and let them do their jobs but remained very engaged in the process, calling, e-mailing, and asking questions.

While we knew a lot of information about St. Paul’s academics, sports, and ideals of serving the world, in hindsight, we didn’t really know anything of the daily culture even after having a child attend for three years.

Looking back, we are painfully reminded of the questions we didn’t ask when we sent our daughters to St. Paul’s School, and the assumptions we made:

Those assumptions and unasked questions have had a huge impact on all our lives. We learned the answers in the hardest way possible.

We encourage parents and guardians to take the time to learn what lies beneath the veneer of any institution—whether it’s a boarding school, college, or summer program. Ask the questions we wish we had asked: What traditions does the school culture hold near and dear? How many sexual assaults are reported? What training is provided to administrators, teachers, and coaches? What support is available to victims?

Sex is a part of the school curriculum, whether it’s official or not: jokes, teasing, social media, and real pressures—along with devastatingly criminal games of sexual conquest and predation. Parents must have conversations with boys and girls from a young age about what consent and healthy relationships mean. It’s not enough to wait for schools to take the lead.

The conversation has to be shifted away from blaming the victim: Why did you drink too much? Why did you go with him? What were you wearing? Instead, we need to talk about changing the behaviors of the perpetrators. In particular, mothers and fathers need to talk to their sons about respect, entitlement, and consent.

We have grappled throughout this journey with how to explain sexual assault in age-appropriate ways to Chessy’s younger sister, Christianna. She was just seven when her sister was assaulted, and we had never discussed sex or sexual assault at that point. It has been very important to us as parents to convey what Chessy experienced and how her sister has struggled and fought to regain a sense of control over her life.

We started with “a young man at school hurt your sister, and the authorities are asking him to take responsibility.” But suffice to say, we were so encouraged by her role in coming up with the #IHaveTheRightTo initiative, and her simple statement: “Sounds like it’s time for a girls’ bill of rights!” It’s a good step in the right direction. The conversation is ongoing.

Be there, be present for the survivors in your life.

Some days, it has been easy to figure out what to do to support Chessy. We tried to show her in words and action that her family’s love for her is stronger than the hateful crime against her, against her body.

We bound ourselves together with the things that make Chessy tick and make her an integral part of our family dynamic of three daughters: her incredible love of all kinds of music, food, her sense of humor and distinctive laughter; her encyclopedic knowledge of funny YouTube videos and pop culture; her love of sports, all things Japanese, babies and children, and puppies. Her ever-growing and inquisitive faith. And, more recently, we’ve had much discourse on the political landscape with our children, to engage them in their futures, and what kind of world they want to live in.

Other days, it was and is still difficult to know what to do to help ease her pain, except be with her. Or nearby. We are not perfect and are certainly not experts in any way—just parents who love their children. The journey after sexual assault to survivorship is jagged, not linear. At this stage of our lives, we depend on love and faith to guide us and hold us together. And we continue to educate ourselves on how rape culture thrives and ways to combat it.

No one wants to believe it can happen to them, to their child, sister, mother, aunt, friend. We understand that, and also had that mind-set. But the fact is quite different. It has happened to someone close to you. But they have remained silent, like so many other victims.

To teens and survivors, we parents are often not perfect—but we can be a good place to start. Communicating with a trusted teacher, an adult in your church or religious community, a mature friend, or older sibling can make all the difference. You are not alone, nor should you be. You deserve love, compassion, and support.

You deserve information on what your options are to move forward. Gather more information, not less. Call your local rape crisis center. Find out about the statute of limitations. In many places, you can get a rape kit test done now and decide later whether you want to pursue the case in criminal court.

Every victim and circumstances are unique. Every family’s experience is unique. Everyone has a story, and they are all a little different—but this is what motivates us to shine a light, to recognize you are not alone in searching for your right to justice and healing.